History

Turkey Run State Park

Find out more about the history of Turkey Run State Park, which is Indiana’s second State Park.

Turkey Run State Park History

The first parcel of Turkey Run State Park‘s 2,382 acres was purchased during Indiana’s centennial in 1916 when the State Park system was first established. Turkey Run is Indiana’s second state park.

There are many legends about how Turkey Run got its name. One story says that wild turkeys, finding it warmer in the canyon bottoms, or “runs”, would often huddle in these runs to avoid the cold. Pioneer hunters would herd the turkeys through these natural funnels into a central location for an easy harvest. Since historic accounts suggest that large numbers of turkeys lived here, it follows that turkeys in the runs prompted the area’s name, Turkey Run.

The early pioneers have also left traces of their heritage here. Find out more about the historic sites at Turkey Run State Park.

A Short Video by a Naturalist explaining the History of Turkey Run State Park

Historic Park Documents

Lovers of Turkey Run State Park history will enjoy these park brochures dated to 1930:

Turkey Run State Park

A History and Description

Department of Conservation

State of Indiana

1930

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction

- The Acquisition of Turkey Run State Park

- The Park’s Facilities

- Nature Guide Service

- The History of Turkey Run

- John Lusk

- Geologic History

- The Trees of Turkey Run

- The Wild Flowers of Turkey Run

- The Birds of Turkey Run

- Trails and Trail Distances at Turkey Run

- Distances to Various Points of Interest in Turkey Run

- Interesting Places at Turkey Run

- Park Rules

“I come here to find myself – it is so easy to get lost in the world.” – John Burroughs

INTRODUCTION

Nearly two thousand years ago Pliny, in a letter to Gallus, wrote this: “Those works of art or nature which are usually the motives for our travels by land or sea are often neglected if they lie within our reach—whether it be that we are naturally less inquisitive concerning those things which are near us; or, perhaps, that we defer from time to time viewing what we have an opportunity of seeing when we please.”

The Department of Conservation, with the splendid co-operation of the citizenry of Indiana, has undertaken to preserve for our present enjoyment, and as an heritage to those who follow us, those rare bits of scenic loveliness, or those hallowed historic shrines, which would otherwise have paid the penalty of our inherent racial neglect. Through the public press we have been taught to appreciate “those things which are near us,” and we marvel, increasingly upon each new rendezvous with Indiana, at the scenic beauty and historic importance of our erstwhile neglected possessions.

Most Hoosiers remember, as though it were yesterday, the heroic fight waged by a few folk of rare vision to save Turkey Run from utter ruin. “The measure of a master,” says Emerson, “is his success in bringing all men round to his opinion twenty years later.” The battle of Turkey Run was a bitter first engagement, and one does not forget the men and women whose heroic efforts here, served to usher in a new epoch in conservation. From this beginning has developed the great system of state parks and publicly owned domains which has been the envy and inspiration of other states.

All this has not simply “happened.” It has meant years of patient plodding, over paths beset by difficulties. It would be a shortsightedness, indeed, were we to forego a grateful tribute to those members of the Conservation Commission and to Col. Richard Lieber, its sole Director, whose years of faithful, unselfish service have served definitely to establish a conservation program ahead of our time, looking far into the future. What has been done already is unbelievable. Within a few years, and with strict economy, many past hopes have become realities—and we are devoutly appreciative and thankful.

Come grey days, when nerves push into each other and families cease to be upon speaking terms. City noises distract, or our own small horizon closes in upon us. In the offing is a state park, in which we hold common stock, where we may taboo intensive civilization and live a while in the lap of nature. So numerous, now, are our parks—and so diversified in character—that one may spend weeks, without flagging of interest, in making their circuit. We may personally conduct ourselves from one charming landscape to another; or commune with the shades of those historic characters who have made history upon the spots they have trod. We have learned that Indiana’s history is the nation’s history, and that the men and events which we have considered as foreign to ourselves have evolved from our own soil in large measure.

It is for us to make the most of our opportunities. Whether we wish, simply, to let ourselves down from high-tension—to take advantage of the playgrounds which nature has provided; or if bent upon the more serious engagements of study and research—our desires have been anticipated and our material comforts provided for. Our parks belong to all of us—they have become a part of the fabric of our citizenship.

—E. Y. Guernsey.

THE ACQUISITION OF TURKEY RUN STATE PARK

In the latter part of the year 1915 a small group of enthusiasts, composed of Richard Lieber, Juliette Strauss, Dr. Frank B. Wynn, Sol S. Kiser and Leo M. Rappaport, conceived the idea of raising a fund by popular subscription to be used for the purchase of Turkey Run and to present the property to the State of Indiana the following year as a centennial gift. At this time the estate of the former owner was in process of settlement, and it was known that the property would be offered at public auction the following spring.

Efforts were made to interest people throughout the state, but it was soon found that the actual money raising would have to begin in Indianapolis. Accordingly, a group of business and professional men was called together for luncheon at the Commercial Club of Indianapolis, where the project was presented. No one seemed willing to start the subscription list, and finally one of the members of the original group made the first offer to subscribe $100.00. Immediately another man in the group criticised the offer as setting a pace which was too high and stated in proportion it would appear as though his subscription should be at least $250.00, and that he did not feel like subscribing so large a sum. The matter was debated at some length and finally Mr. J. D. Adams, who had been reared in that part of the country, came to the rescue with the statement that under all circumstances this property should be acquired, and that he was willing to make a donation of $500.00. With the ice thus broken the committee had its start and eventually succeeded in raising a total of $20,000.00.

The auction sale took place in April, 1916. Lumber dealers throughout the state had been asked to refrain from bidding. The appraisal on the property was in the neighborhood of $15,000.00, and the committee felt certain that it not only would be able to buy the property but that it had sufficient funds with which to pay for the same. It soon found, however, that it did not have a clear course. Another bidder appeared, representing a lumber company, who wanted the property solely for commercial purposes, and after a spirited contest in bidding the property was knocked down to him for $30,200.00.

The original committee did not lose its courage and immediately began negotiations with the purchaser, who offered to surrender the property to the state after he had stripped it of its valuable virgin timber. This the committee indignantly declined. Eventually it received from him an offer to sell the property, intact, at an advance of $10,000.00. This meant that more funds would have to be raised. In October, 1916, the committee succeeded in interesting Mr. Carl G. Fischer sufficiently to cause him to view the property. A whole day was spent in going over the scenic beauties of this tract of land, and by evening Mr. Fischer very generously offered to donate the sum of $5,000.00 and also to propose to the Board of Directors of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway that this company donate 10% of the proceeds of the next Decoration Day race. He was successful in this matter and great credit for this contribution is due not only Mr. Fischer but Messrs. Arthur Newby, James A. Allison and Frank H. Wheeler, who were Mr. Fischer’s associates at that time in this enterprise. Furthermore, Mr. Newby made a personal donation of $5,000.00, and in later years helped to purchase some land adjoining the state park.

With these added funds, plus a part of a $20,000.00 appropriation by the General Assembly of 1817, the committee was in a position to complete the purchase of the property, and on November 11, 1916—a day which has since become historic in world affairs—signed the papers for that portion of the property, viz.: 288 acres, constituting the original state park.

—Leo M. Rappaport.

THE PARK’S FACILITIES

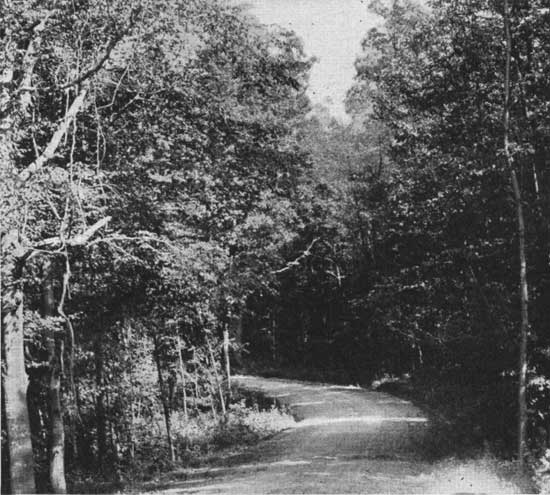

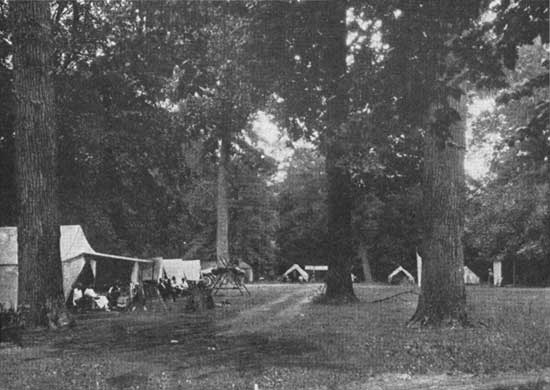

Turkey Run State Park now comprises 1,150 acres, nearly all of the area is heavily wooded, and 285 acres of the tract are of virgin timber—in which there has never been any cutting. Taken as a whole, it represents one of the finest forest areas in Indiana or, for that matter, in the Middle West.

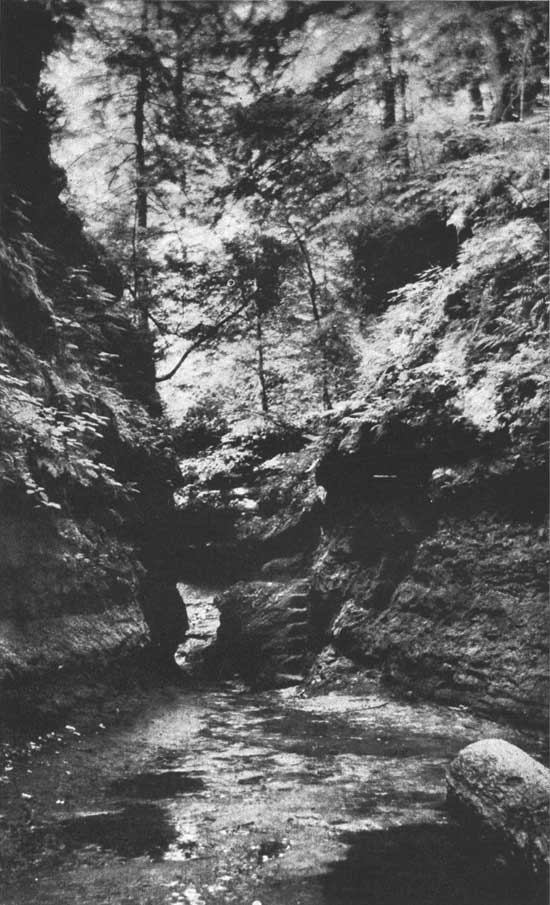

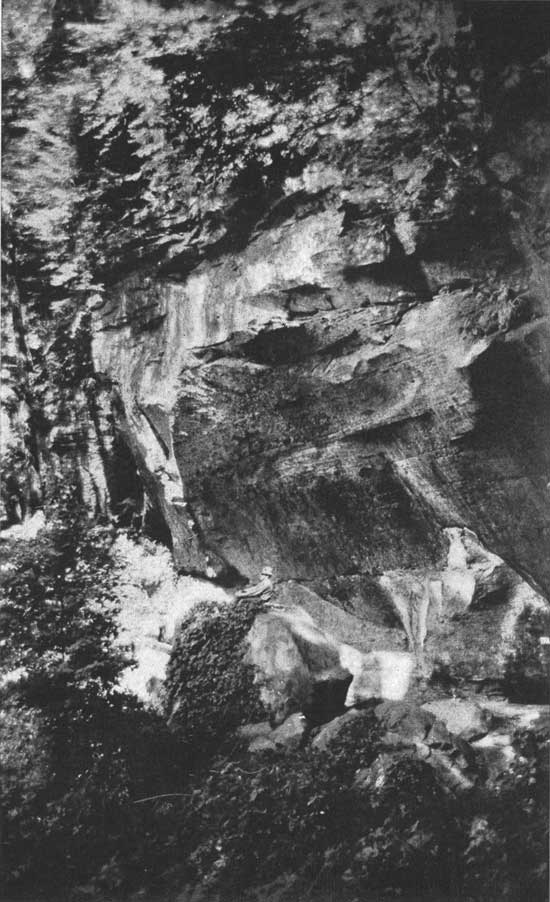

The situation, along both banks of Sugar Creek in upper Parke County, provides a natural setting, rugged in character, for which glacial action is responsible. High walls cut from the solid rock, to which cling myriads of small plants and wild flowers, overshadowed by the massed, lace-like foliage of the hemlock, present a changing vista of rare beauty.

To reach Turkey Run one should follow State Road 41, from which a short connecting road brings one to the park gates. If coming by rail, train service is available to Marshall over the B. & O. Railroad, thence one takes motor livery for the three remaining miles.

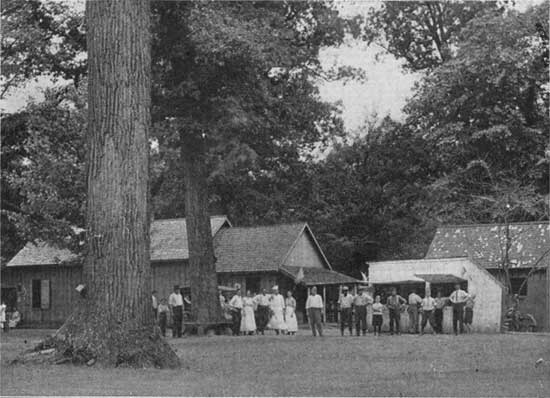

At Turkey Run ample provisions have been made for the comfort of the thousands of guests who come to the place yearly. Turkey Run Inn is the original state park hotel, and has been long noted for the excellence of its simple service. Recently the Inn has been greatly enlarged and improved, and now provides 100 comfortable and commodious rooms. The new dining room, with an enlarged and thoroughly modern kitchen, has been planned to render prompt and efficient service at all times and to meet all emergencies. In addition to the facilities of the hotel a number of cottages have been provided. These contain sleeping rooms only. They will be found comfortable and convenient for those who prefer the more secluded quarters which they offer. Turkey Run’s famous chicken dinners are served on Sundays. Reservations should be made to TURKEY RUN INN, MARSHALL, INDIANA.

Ample parking space has been provided at the park and provision has been made for those who bring their own tents or outdoor sleeping equipment. Fireplaces, water and wood are provided for campers, dressing rooms for bathers, and there is absolutely pure drinking water supplied from driven wells. A playground has been installed for the benefit of the smaller children.

NATURE GUIDE SERVICE

In the park are 30 miles of foot trails which lead to many points of scenic and historic interest, such as Rocky Hollow, Turkey Run Hollow, Log Cabin, Log Church and Walnut Grove. These trails are plainly marked and numbered so that they may be easily followed. Small trail maps may be had at the hotel.

A Nature Guide Service was instituted at Turkey Run in 1927, since which time it has continued, during the months of June, July and August, with a marked increase in popularity. This service, which is free to all, has served to familiarize the park’s many visitors with the various interesting details of animal and plant life not usually discoverable to those who have not specialized in nature study. The lectures, en route, are not technical or ultra scientific, but are intended to convey accurate information to the average park guest as well as to those who have a more definite interest in scientific study. The daily “nature hikes,” starting from the hotel at 8:30 a. m. and 1:30 p. m., are comprehensive in character and are meant to help the visitor to a general appreciation of the interesting natural and historic features of Turkey Run. On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays parties are conducted to those secluded portions of the park where one may best hear the song of the summer birds. Even though this necessitates the setting of alarm clocks at 5:00, the experience is one not soon to be forgotten.

Where it is not found convenient to accompany the nature guide upon his journeys about the park, silent nature trails have been provided. This means, simply, that the interesting features along the various trails have been plainly marked so that one may take the trails leisurely and alone, depending upon the printed data to inform him of the points of interest.

Each night of the week, except Saturday (which is given over to the usual weekly dance), lectures are given at the hotel. The subjects vary but are so chosen that interest does not flag. Moving pictures and photographic slides are used to illustrate these lectures.

“Time flies and draws us with it. The moment in which I am speaking is already far from me.”

– Boileau.

THE HISTORY OF TURKEY RUN

The Indian name for Sugar Creek, it is said, was Pungosecone. Although the authority for the name has not been obtainable, it has been derived from the Algonquin and is probably compounded from the Lenape words “pungo” or “pungh,” and “saucon” or “sakunk”—which, together, refer to ashes (dust or gunpowder) at the mouth of a stream. Though one must always conjecture, more or less, upon the intent of such Indian words, it is probable that this has some legendary or traditional import, most likely connected with the discovery of the burnt ruins of a former Indian settlement at the mouth of Sugar Creek. Hough has applied to Sugar Creek the supposed Miami name, Keankiksepe, the meaning of which is not quite clear. In the Lenape dialect the word for sugar was “schiechikiminschi,” and the former word is possibly a corruption from a similar Miami word, with the terminal “sepe,” which means a river or creek. It is well known that we are indebted to the Indian for the discovery of the process of making sugar from the sap of the maple tree, and it is probable that the tribes in the vicinity took stock of the abundance of sugar-making material at hand, as did the white settlers who followed them.

Before the days of the first white settlement, and for some years afterward, the vicinity of the present Turkey Run was a favored haunt of the Indians. There were long established villages of the Kickapoo, Piankeshaw and Wea nearby. In Parke County, too, was the reservation of Ambroise Dazney, who had seen service at Kaskaskia and Tippecanoe, and who was a valued friend of Governor Harrison. His wife was Meshingomeshia—”the beautiful burr oak”—a Miami of historic importance. Her brother, Jocco, was the head of the Wea band of Miamis who lived at “Old Orchard Town,” near the present site of Terre Haute, which tribe later removed to the Sugar Creek reservation. This reservation fell, in time, to Christmas Dazney, a son of Ambroise and Meshingomeshia. He was exceptionally well educated, spoke English and French with fluency, and was master of the various dialects of the Indiana and Illinois tribes. He served for many years as government agent and interpreter at Fort Harrison. His wife was a Mohegan woman of refinement and education.

Near Rosedale was the historic mission of Rev. Isaac McCoy. Thus it may be understood that Turkey Run and its environs were, in a large degree, concerned with the history and legend of the red man. The pioneer white families found an acquaintance with these sedentary and peace-loving tribes more to be cultivated than shunned. Such men as Christmas Dazney were, in fact, superior in education and acumen to most of their white neighbors, as was often the case where there was an admixture of Indian and French blood.

* * * * *

To this sparsely settled region came Captain Salmon Lusk with his bride, who had been Polly Beard. This was in the spring of 1821, after the debacle at Prophetstown had relieved the danger of residence in northern Indiana. Captain Lusk was a Vermonter who had ventured into Indiana at an early date, had enlisted in the army of General Harrison, and had participated in the battle at Tippecanoe. For military services rendered his country he was granted a patent to a parcel of land, probably of his own choosing, in the Sugar Creek country. For a number of years after the defeat of the Prophet a military post was maintained at Fort Harrison, above Terre Haute, and it was from this post that Lusk and his wife came, traveling upon horseback, as was necessary when the only roads were often mere trails through the forest.

It may he presumed that the picturesque beauty of the region about the Narrows to which he came appealed strongly to this young man from the Green Mountains—besides, it offered advantages which young Lusk seized upon with the instinct of his ancestry. The site was ideal for water power, and he constructed a grist mill as a first impulse.

In those days New Orleans provided the chief market for flour and meal and for cured meat. The annual spring freshets enabled him to convey these commodities by flatboat down to the Wabash, thence to the Mississippi. Not the least valuable commodity of these cargoes was the flatboat itself, which was, in fact, a raft of yellow poplar timber, useful in building construction and utilized under the name of “tulip wood” by the cabinet makers of the old South. Captain Lusk prospered and expanded in his enterprises. The Narrows became a trading point for the surrounding country. The usual general store became a necessary adjunct, and a tavern was set up to minister to those pioneer tradesmen who came that way en route to New Orleans. Here rough characters sometimes congregated, and many stories are told of the high play at cards which sometimes ended in the loss of valuable cargoes through an hour’s gaming.

Until 1847, when the great flood in Sugar Creek swept away the mill and surrounding buildings, business activities continued. This catastrophe ended forever the life of “Lusk’s Mills.” Traces of the former tavern still remain opposite the old mill site, but there is virtually no evidence left of the once thriving business center. The ingenuity of the day in which “necessity became the mother of invention” is interestingly illustrated at the site of the former mill. Here, where the entire structure was set upon a massive deposit of sandstone, the millrace, as well as the supports upon which the timbers rested, have been carved from the solid rock.

The original Lusk homestead at length gave way to a more pretentious residence, now one of the landmarks of western Indiana. It was erected upon the site of its predecessor of the best material which the locality offered. The bricks for the new structure were burned upon the spot, and are today as well preserved as when brought from the kiln. Clear yellow poplar furnished the frame work, and for the interior trim selected black walnut was deemed the only wood worthy of use. There was no skimping of material, and the house will stand for generations to come.

In 1869 Captain Lusk died, leaving to his son, John, the residence which he had completed nearly thirty years earlier, with one thousand acres of land contiguous to it. Here Polly Lusk died in 1880, the son, John, passing in 1915. To this eccentric individual and his pride of inheritance we owe the preservation of one of the few unspoiled landscapes in Indiana. To the right of the entrance to the Lusk home the Nature Study Club of Indiana has affixed a tablet bearing the legend: “To the Memory of John Lusk, who saved the Trees of Turkey Run.”

“There is no such thing as solitude, nor anything that can be said to be alone and by itself, except God.”

– Sir Thomas Browne.

JOHN LUSK

The dividing line between eccentricity and genius is the merest thread. A twist in another direction would perhaps have made of John Lusk another Thoreau. He loved his heritage—as is to be expected of one who has grown up in the lap of nature. He cared little for men—not at all for women. An analyst would say that he had the “mother complex,” for he revered her above all persons. Upon her death in 1880 the mother’s room was closed, to be left as it was when the unseen guest entered. Thereafter Lusk lived the life of a recluse, confining his occupancy of the house to a single room. Here he lived—preparing his own simple meals and paying no heed to the niceties of housekeeping. He read the Bible, an heritage of his pioneer ancestry, and merely scanned the newspapers which came to him. For books, in general, he cared little. The papers he threw aside to accumulate in vast, disorderly heaps. It became necessary to dig out from this impedimenta, upon occasion, as one makes a path through the snow.

It is said that John Lusk was profane at times, as could be anticipated from one who had the stamina to resist the importunities of nature spoilers who wished to convert his beloved trees into joists and scantlings.

In the colorless “eighties,” when folk walked afield and bicycling became a near mania, Lusk’s woods came to be a popular resort. In those days the place was known as “Bloomingdale Glens,” and the name clung to it for years thereafter. The old Indianapolis, Decatur & Springfield Railroad conceived the idea of converting it into a summer resort. Excursions were run to the Glens, an eating place was established and tents were set up for those who wished to tarry for a day or so. Financial difficulties forced the company to abandon their lease and one William Hooghkirk continued to operate for several years upon the same plan. In 1910 it was leased again, to R. P. Luke, under whose and Mrs. Luke’s management the place waxed in popularity and became the mecca for visitors from near and far.

In 1915 John Lusk died after having successfully resisted the temptations, if he ever seriously considered them such, to let down the bars to timber vandals. Money, to him, was of little value—the preservation of the place of much. Visitors were at all times welcome, for he seemed to have a strange pleasure in the thought that others were interested in and appreciative of the natural beauties of his possession. Thus, for thirty-five years did this eccentric individual stand guard over his heritage. Perhaps, after all, he was less whimsical than we are prone to believe him. At all events Indiana, in this day of grace, respects his memory.

“Now we learn by what patient periods the rock is formed. It is a long way from granite to the oyster.”

– Emerson.

GEOLOGIC HISTORY

The geology of Turkey Run may be said to have begun when the great masses of sandstone, from which the gorge is carved, were deposited upon the vast inland sea which covered this area during the time when coal was being formed. After the deposition of this sandstone, which geologists call the Mansfield, this great sea became shallow, being replaced by marshes of no great depth. In these marshes, under tropical conditions, a rank vegetation sprang up. Here flourished the lordly evergreens of Carbonic time—the Lepidodendron (sometimes called the “Scale Tree”) and the Sigillaria, whose trunk bears a delicate seal-like impression upon its surface. More than a hundred varieties of the former have been described, some of whose trunks have measured a hundred feet. The latter, the largest of carboniferous trees, bore trunks reaching six feet in diameter and more than a hundred feet in height. Here, too, grew the Calamites, or giant rushes, and tree ferns of bewildering variation. This accumulated vegetation was at length buried under subsequent deposits and later transformed into coal under the great pressure which resulted. Following this came marine conditions similar to that which exists under our present seas until several hundred feet of sediment had been deposited above the massive layer of Mansfield sandstone. Later this sea receded permanently and land conditions prevailed. Then followed a long period of weathering and erosion, during which time prodigious layers containing coal, hundreds of feet in thickness and overlying the sandstone, were removed. The reader will realize that we are talking, not in hundreds and thousands of years but in geologic ages when we speak of these various phases.

Ages, then, went by—ushering in new events. The climate gradually changed until it became very cold, approximating the present Arctic conditions, until, upon the scarred surface of the Mansfield sandstone, there rested thousands of feet of ice which, moving slowly southward, cut deeply into the sandstone upon which it rested. Again the climate became mild, the ice retreating meanwhile and at length disappearing. In its wake were deposited immense quantities of loose sand, gravel, clay and boulders, brought from the far North—filling in the former valleys and destroying the existing systems of drainage. During this process the raging water carved new channels for itself, establishing an entirely new drainage system.

Sugar Creek was one of these newly made streams and became a part of the new drainage system, cutting its way easily through the drift deposit and on through the underlying sandstone. The surface water of the region, now assuming the proportions of a devastating flood, concentrated at a depression along its course, which point was the beginning of Turkey Run. Through thousands of years, subsequently, the erosional force of water has been continued, lengthening and deepening the gorge thus formed. The upper layer of sandstone, more resistant because of compounds of iron and silica which cemented and strengthened it, has disintegrated less rapidly than the underlying strata; so that the gorge has not widened as rapidly as it has deepened. The erosion of the softer layer underneath has been augmented by cracking and splitting due to freezing, with the result that the gorge is often wider at the bottom than at the top.

Thus, to geologic processes, we owe much of the charm of Turkey Run. These varying phases of the earth’s history may be studied with ease and certainly with profit by the non-scientific visitor. The erratic boulders which one picks up, carried upon the glacier’s back from the “Land of Snows,” may tell us somewhat of their former habitat and much of the uncanny force of glacial action. Along the stream channels may be found numerous cauldron-like basins in the sandstone. These are the so-called “glacial mills,” which are precisely like those which may be seen in the famous Glacier Garden of Lucerne. They are the result of the erosional action of glacial cataracts which, with the aid of the abrasive force of stray boulders caught in some rock depression, have whirled about till the softer rock mass has been hollowed as with a chisel—the abrading boulders assuming the shape of an almost perfect sphere. Then, too, one may chance to discover some lingering souvenir of the coal-measure era—a fragment of some once living plant—now a sermon in stone. To the diligent searcher after knowledge here are opportunities galore.

At a number of points along Turkey Run, particularly through Newby Gulch, one may observe examples of the curious and interesting formation known as calcareous tufa, sometimes improperly called tuff. Underground water, and surface water as well, often possesses great disintegrating force. In this state it dissolves more limestone than it can carry away in solution—thus percolating waters throw down a deposit of calcareous limestone which, upon exposure to the air, hardens into a compact mass. If there is a rapid motion to the water, as when it is dashed into spray in a cascade, carbonic acid gas is liberated—thus rendering the lime insoluble and hastening the process of deposition.

If we were to examine one of these newly made rock masses we should find it to consist of fragments of wood, broken twigs, leaves, mosses and other organisms, coated over with the deposited lime—or in a complete state of petrifaction. Thus it is possible, at Turkey Run, to study the actual processes through which fossils have been formed. The formation of tufa is often quite rapid, as, for example, there are certain deposits in Sicily in which the rate is one foot in four months.

If it were possible to look upon the Turkey Run of interglacial times we should have much difficulty in recognizing the fauna which existed here. Today, in northern Indiana, workmen often come upon the semi-fossilized bones of these creatures buried in some glacial deposit, from which we are enabled to definitely determine the character of animal life which existed here before the advent of man.

Of the elephant tribe we have the mammoth and mastodon—cumbersome creatures akin to our modern species. The musk-ox, or ovibos, once made this region their habitat—though now found only in the far North, much varied in type. The giant beaver, or Castoroides, would have dwarfed his modern descendant. Strange as it may seem to us, the camel once flourished here, though quite different in form from that with which we are familiar. The giant sloth, in many variations of size and bearing an armor-plate of small bones secreted under the skin, crippled his way through the Indiana forests; his claw-feet bent inward so that he must walk upon their sides.

It would be tiresome to mention the wide variety of animals and birds which were indigenous to northern Indiana when Turkey Run assumed its present contour. It is interesting, though painful to our state pride, to know that many of the notable specimens of these extinct creatures were first discovered in Indiana, but grace the museums of other states. Many notable collections secured at great expense in Indiana have found their way to foreign museums, while our own state has not yet provided a fitting building in which they might be preserved for all time.

“No tree in all the grove but has its charm; Tho each its hue peculiar.”

– Cowper.

THE TREES OF TURKEY RUN

When one possesses trees of the height and girth of those in Turkey Run the gods should be thanked—not forgetting, of course, the men of rare vision who have preserved them. There are so few remaining remnants of primeval forest in Indiana that they may be counted upon the fingers, with digits to spare; How rare is the Tulip tree, that cousin to the Magnolia, which stands alone in its genus in America. When Freeman made his historic survey of the “Vincennes Tract” in 1802 he recorded seeing these trees 200 feet in height and 10 feet in diameter. The largest Tulip tree in Turkey Run has a circumference of over 14 feet, which is rare in these days. No forest tree seems so erect and stately—when in blossom it justifies the wisdom of Indiana’s choice of her state flower, for it is as interesting in structure as it is beautiful.

Most of the trees in Turkey Run belong to the “Hardwood,” or broad-leaved group; but upon the tops of the higher bluffs are found the Hemlocks, commonly called Firs, which are among the rarest trees in the state, here found in great abundance. The foliage is as delicate as old lace and vibrates to the slightest breeze. Their spider-like root formation may be observed along the gorges, where they have reached out like tentacles for support. The Yew tree, also an evergreen and very rare in the state, hangs from the cliff edges down into the hollows. In the fall its red berries are conspicuous.

The largest tree in the park, and there are more than a hundred with a circumference of over seven feet, is the “Big Sycamore,” on Trail 1. This hoary veteran has a girth of 20-1/2 feet and seems to belong to some other country and age. In winter, after the brittle bark has flaked off, the sycamores along the water’s edge look as if splashed with whitewash by some careless painter. Some of our Indiana artists, not pledged to the beeches, love to paint the sycamore, deeming it the most satisfying of trees in the effect obtained. Next in size to the sycamores come the black walnuts, then follow the white oaks, the elms and the hackberries.

One may roam here for hours through deep woods and canyons, each turn of one’s steps presenting new pictures of un usual beauty. Grey-splotched beeches throw out their long, graceful branches, which terminate in polished silvery filaments. One can not say whether they are lovelier in the green leaf of spring or when the first frosts have turned their foliage to russet and gold.

In Turkey Run is probably the largest Wild Cherry in the state, the trunk rising to a height of ninety feet, straight as a Poplar. These waxen-leaved trees, with foliage of the darkest green, served an utilitarian purpose in pioneer days, when their soft but tenacious wood became the joy of the early craftsman. It has been called “The Mahogany of the Pioneer,” and many rarely beautiful turned and reeded furniture pieces, their color softened by age, have come down to us from our ancestors.

With the first advent of spring the Dogwood becomes a showy cloud of white blossom, replaced in mid-summer by clusters of green berries, which autumn turns to crimson. Here, where it is not permitted to break off the showy branches, the Dogwood is seen in its pristine beauty. Elsewhere thoughtless people have nearly destroyed these lovely trees, which are becoming rarer each year through the onslaughts of those who think only of the moment.

The Red Bud, which really belongs to the Locust family, dominates the spring landscape, where it congregates in thickets on the outskirts of the woods, its rose-purple blossoms contrasting with a background of green. It is one of the first of the blossoming trees to hoist its colors to the breeze. The Wild Crab, the Juneberry, or Service Tree, the Haws and the Pawpaw lend their individuality to the picture, each inviting the visitor to take note of its peculiar beauty or interest.

One should learn to know the trees by name and go into the finer details of bark, blossom and leaf structure to really enjoy them. They are to be “lived with and loved,” as John Muir has said. It is interesting to know, for instance, that the Persimmon is a brother to the Ebony. When we admire the delicacy of some rare wood engraving we will be grieved, perhaps, to know that some fastidious Dogwood has been sacrificed to provide the block upon which it has been cut. The common post-card, which Uncle Sam sells us for a penny, has derived its tough and unabsorbent surface from the crushed fibers of the Tulip tree.

Our vacations at such places as Turkey Run are unfruitful if we do not profit from the more serious purposes of nature study, for which they offer a full measure of reward to those “immortals” who live to learn.

“And because the breath of flowers is far sweeter in the air than in the hand, therefore nothing is more fit for that delight than to know what be the flowers and plants that do best perfume the air.”

– Bacon.

THE WILD FLOWERS OF TURKEY RUN

The wild flowers of Turkey Run—how they delight our senses by their delicate beauty and the wide variety of their coloring. Their subtle fragrance belongs to the forest recesses where they thrive. It would seem that all the wild flowers in Indiana had congregated here. Dr. John Coulter, Indiana’s own beloved botanist, has told us how many of our wild flowers have “moved” from other states, and from regions far remote from us, so that we may trace the migrations of our flowers as we do those of our pioneer families.

Very early in the spring a race is run for the honor of being the first to bloom—the Spring Beauty, Hepatica, Adder’s Tongue, Anemone and Bloodroot striving for honors. Two relatives of our cultivated flowers enter the lists, the quaint Dutchman’s Breeches and the little Squirrel Corn—both near kin to the Bleeding Heart of our gardens. In the lowland the Virginia Cowslip, or Blue Bells, grow in showy clumps.

Quite soon follow the Rue, Anemone, the white and purple Cress, Violets—blue, yellow and white—the waxy Trilliums in a wide variety of form and color. The Fire Pink, with its red star-shaped flower, prepares the way for the pale or spotted Jewel Weed, which blooms in mid-summer.

The succession of flowering beauties is continuous. The dainty Dogtooth Violet, the Cypripediums, which belong to the Orchid family and are known to us as the Moccasin Flower and Whip-Poor-Will’s Shoes, the Chick Weeds, Wild Blue Phlox, Stonecrops, Wild Ginger and Pepper Root, the Celandine Poppy, ask for our more intimate acquaintance. The Greek Valerian, which nods like the Blue Bell, the Hound’s Tongue, which has come to us from Asia, and the Beeksteak Plant, or Lousewort, which hails from the East, each appeals to us because of its individuality and associations.

Among the flowering shrubs are the Leatherwood, which has an affinity for the high banks of streams and bears a modest blue flower. The Spicebush, which is in fact a Laurel, covers the slopes with a massive green foliage, its yellow flowerettes appearing before the pungent leaves shoot out. Both of these shrubs bring thoughts of bygone days, where, in pioneer times, they served economic purposes. The tough bark of the former provided thongs for mending harness and for tying bundles, and the latter, beside its medicinal use as a tea, was used in lieu of allspice, the dried buds offering a competent substitute in revolutionary time and after.

In mid-summer the wild flowers become less conspicuous, but late summer ushers in a new riot of color. The Wild Plum, the Wild Crab, the White Bladderwort precede the Cone Flowers, the Asters, the Iron Weed, the Joe Pye Weed and several varieties of the Golden Rod. The Wild Bergamot, which has a refreshing mint fragrance, and the Wild Hydrangea give a delightful color scheme of lavender and white.

The Lobelia, Sunflower and Wild Lettuce come at this time, as do the charming yellow flowers of the Toadflax, commonly known as “Butter-and-Eggs.” In the uplands under beech trees may be found the parasitic Beech Drops or Cancer Root, and under the hemlocks on the high ridges may be seen in profusion the delicate white, pipe-shaped plants of the Indian Pipe. This colorless wax flower, sometimes called the Ice Plant, grows also in Japan, when the native artists seem to have become fascinated with its chaste but mysterious charm.

To enumerate the flowers of Turkey Run would be as tiresome as the compilation of a dictionary, for more than four hundred varieties of herbaceous plants alone have been found here. A check-list of its wild flowers would fill a volume. Perhaps no other branch of nature study will so fully repay the adventurer into its realms as that of botany. Here, at Turkey Run, may be found a true botanist’s paradise.

“This great solitude is quick with life; And birds that scarce have learned the fear of men Are here.”

– Bryant.

THE BIRDS OF TURKEY RUN

What the bird population of Turkey Run must have been in an early day would demand the imagination of a true naturalist. Today, including the migratory species and those who pay chance visits, nearly two hundred varieties have been registered by Mr. Sidney R. Esten, who is upon intimate terms with these bird friends of man.

In Audubon’s day, and as he and other early naturalists and travelers have recorded, vast flocks of Wild Turkey, Carolina Parrakeets and Passenger Pigeons were native to Indiana. The last two, with the magnificent ivory-billed Woodpecker, have succumbed to the persecution of man and are known to us only through the pathetic specimens preserved in museums. One of the last remaining colonies of Parrakeets is reported to have been found northwest of Lusk’s Mills in the winter of 1842 by Mr. Return Richmond. Mr. Richmond, upon felling a hollow sycamore tree, discovered several hundred of these birds, who had taken refuge within the hollow trunk and were so chilled from the cold that they were unable to move. In order to prevent the birds from freezing Mr. Richmond sawed off a section of the trunk containing the birds, which unwieldy cage he rolled to his home, covering the ends with netting. Upon the return of clement weather they were set free.

The Wild Turkey, indeed, was so numerous as to give rise to the name of Turkey Run. What is now called Turkey Run Hollow served in an early day as a place of refuge for thousands of these birds; whose “roost” was provided by the great rock crevices of the hollow. An early hunting story tells of the discovery of perhaps the largest flock ever seen in the vicinity. The birds were discovered a short distance from the canyon, and to this they escaped. Almost immediately the hunters arrived at the spot, but the birds had disappeared so completely that not one was to be seen. The occurrence is, even today, a mystery, but it is probable that there existed some hidden cavern, yet undiscovered, through which they made their escape.

In the heyday of Lusk’s Mills the Passenger Pigeon was so numerous as to sometimes darken the sky. Thousands of these birds were caught in nets, and the pigeon squabs were packed in barrels and shipped to the city markets for human consumption. The market became so glutted that shipments were refused, and thousands of these beautiful birds were fed to the hogs.

Throughout the entire year the visitor to Turkey Run is permitted to share the society of these graceful songsters who contribute their cheerful voice and their colorful beauty to his pleasure. During the summer months the Cardinal, Robin and the Wood Thrush vie with each other in scaling the upper registers of song. The Phoebe may be discovered carrying provender to their hungry progeny, whose gaping mouths yawn from a well constructed nest attached to some projecting rock. The Chipping Sparrow ventures up boldly to one’s very feet, in quest of seeds or crumbs. Almost as venturesome is the Tufted Titmouse, who scampers over camp tables in search of crumbs. On Monday mornings, after Sunday guests have taken their departure, the Carolina Woodpecker, the Downie and the saucy Jay swing about the refuse baskets, having much ado to keep their balance but managing to gorge themselves to the bursting point.

Along the trails in the spring flashes of color cross one’s path—living bits of red, yellow, green and blue—as the warblers pause on their northward flight. At night, from hotel window or through the tent’s thin walls, one may hear the weird night cries of the Whippoorwill, or the almost human voice of the complaining Owl.

Of nesting birds there are around eighty resident species at Turkey Run, sharing with human visitors the home which nature has provided for them.

There are some sinners among the birds as with the human race, but they are in the minority. Upon acquaintance we find these feathered folk to be charming companions, meeting us half way and repaying courtesies shown them. So human are they that such nature lovers as John Burroughs has given them human attributes, as when he calls the Crested Fly Catcher the “Wild Irishman of the Forest.” We should be thankful for the birds of Turkey Run—there are so few bird friends left us where civilization has been set up—and should pay them our respects and grasp the wing of fellowship which they offer us.

TRAILS AND TRAIL DISTANCES AT TURKEY RUN

There are nine labeled trails in Turkey Run State Park, totaling sixteen miles in length, and fourteen miles of unlabeled trails. To enjoy best the beauties of the park you are advised to wear hiking clothes and low-heeled, serviceable shoes. It takes about five days for the experienced hiker to cover all the trails of the park, as it is necessary in many cases to go over the nearer trails several times to reach the outlying trails.

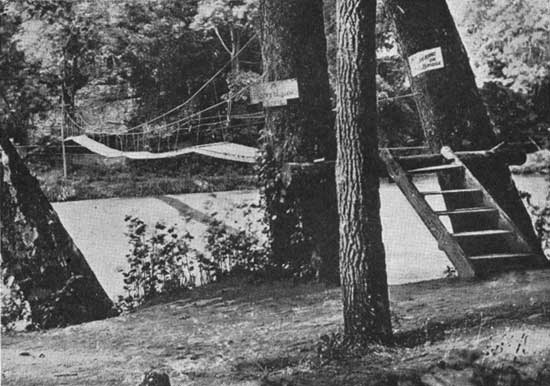

The following list of the trails gives the distance of each from the hotel and return; also some of the points of interest on each. From the hotel to the suspension bridge and return the distance is one mile, and this should be subtracted from the following trail distances if the hike is begun and ended at the bridge.

Trail 1. 2-3/4 miles. Along the south shore of Sugar Creek past the swinging bridge to the covered bridge, then south to road, east along road through campground to hotel. This is a comparatively easy trail with but few places to climb. Interesting places: Lover’s Lane, Hawk’s Nest, the large elms, the sycamore grove, the largest walnut in the park, Goose Rock, Ship Rock, the largest tree in the park, Lusk’s Fill.

Trail 2. 3 miles. Either along trail or through the camp ground and down the steps. From Trail 1 Trail 2 leads up Newby Gulch, across the plateau, across the road (Trails 1 and 2 at this point are together) through the woods for about one-fourth mile, then west through Gypsy Gulch and Box Canyon to swinging bridge and back to campground and hotel. Interesting points: The Tuffa Beds in Newby Gulch, the High Bridge over Newby Gulch, the Overhanging Rock Cliffs in Gypsy Gulch, and Box Canyon and many wonderful ferns.

(For comparison note figure in foreground)

Trail 3. 2-1/2 miles. Take Trail 1 to swinging bridge, and after crossing Sugar Creek go up Rocky Hollow (Trail 4) for about one-half mile, then west through woodlands, down the ladders in Bear Hollow, east by river down ladders in Ladder Rock, back to swinging bridge. Interesting points: Rocky Hollow, Edge Rock, the Punch Bowl, Bear Hollow, the Ice Box, Wedge Rock and Ladder Rock.

Trail 4. 3-1/2 miles. Trail 1 to swinging bridge, thence up Rocky Hollow, turning at the head of the hollow, through woods to Lusk Home on the hill above the Narrows, back to campground or hotel by way of Trail 8 or Trail 3 along Sugar Creek to swinging bridge. Interesting points: Rocky Hollow, Yew Trees, Edge Rock, Punch Bowl, Lusk Home, the Old Mill Site, the Covered Bridge and the Coal Mine.

Trail 5. 4 miles. The same route as that taken for Trail 3. Trail 5 branches out from Trail 3 and extends for some distance west of Trail 3 through the woods. Instead of going up Rocky Hollow, Trail 5 can be reached on Trail 3 by going west from swinging bridge up through Ladder Rock. Interesting points: The Ice Box, Wedge Rock, beautiful woodland scenes with ferns and flowers.

Trail 6. 1/2 mile. From Sunset Point down to Turkey Run Hollow, up hollow to road. This is the shortest trail in the park. Interesting points: The Overhanging Cliffs, under which the wild turkeys came to roost, the Cement Bridge over Turkey Run Hollow and Sword Moss, which is found only in a few places in North America.

Trail 7. 3/4 mile. From Sunset Point down into the hollow, west up cliff around Inspiration Point, through woods and down the hollow to Sunset Point. Interesting points: Mosses, Walking Ferns and Yew Trees, good view of Sugar Creek and Overhanging Cliffs.

Trail 8. 3-1/4 miles. Along Trail 1 to swinging bridge. After crossing bridge go east along creek to coal mine, then north on Trail 8 to junction with 4, east (right) through woods to Lusk Home, west along the edge of field to coal mine and Trail 3 to swinging bridge. Interesting points: Coal Mine, Ferns, Flowers, Lusk Home, Narrows, Mill Site.

Trail 9. 4 miles (via Ladder Rock), 4-1/2 miles (via Rocky Hollow). This is the longest and hardest hike in the park, for in order to reach Trail 9 parts of Trails 3 and 5 have to be taken. Trail 9 extends from Trail 5 west through falls and boulder canyons. Interesting points: The Glacial Boulders deposited many years ago when the great glaciers from the North covered this area. Many of the same points seen on Trails 3 and 5.

DISTANCES TO VARIOUS POINTS OF INTEREST IN TURKEY RUN

From Hotel to Swinging Bridge (via Trail 1 through campground or via Trail 1 along Sugar Creek)—one-half mile.

From Hotel to Covered Bridge and Lusk Home by Trail 1—1-1/2 miles. By automobile—2-1/2 miles.

From Hotel to Box Canyon—3/4 mile. (Trails 1 and 2.)

From Hotel to Gypsy Gulch—3/4 mile. (Trails 1 and 2.)

From Hotel to Punch Bowl—3/4 mile. (Trails 1 and 4.)

From Hotel to Ice Box—3/4 mile. (Trails 1 and 3.)

From Hotel to Goose Rock and Ship Rock—7/8 mile. (Trail 1.)

From Hotel to Coal Mine—3/4 mile. (Trails 1 and 3.)

From Hotel to Big Walnut—4/5 mile. (Trails 1 and 2.)

From Hotel to Big Sycamore—1 mile. (Trail 1.)

From Hotel to Big Tulip—1/4 mile. (Trails 6 and 7.)

From Hotel to Log Church—1/4 mile. (W. along road from west entrance, across cement bridge over Turkey Run Hollow, and through woods by an unnumbered trail.)

INTERESTING PLACES AT TURKEY RUN

1. The Lusk Homestead, the Narrows of Sugar Creek, the Covered Bridge, the Old Mill Site and other points of interest connected with the history of Salmon Lusk, Polly Beard Lusk and John Lusk can be reached by Trail 1 along Sugar Creek or by automobile from the west entrance east to the front entrance and north to the Lusk Home.

2. The State Cabin on Sunset Point is a short distance northwest of the hotel. This cabin was built by Daniel Gay about 1841 and moved to its present site in 1917. Several of the logs of Tulip or Yellow Poplar are 30 feet long, 30 inches wide and 6 inches thick.

3. The Old Log Church is located on the ridge above Turkey Run Hollow. It was formerly used in 1875 and was moved to the park in 1923. It is a sample of pioneer church used by early Hoosiers.

4. Goose Rock, on Trail 1, is between the Covered Bridge and the Swinging Bridge. It is so named because of its resemblance to a goose head, as viewed from Trail 1 east of the rock. The legend of Goose Rock relates that Johnny Green, the last Indian of the area, was shot as he sat fishing on this rock.

5. The Swinging Bridge across Sugar Creek was built in 1918. It is 4 feet wide and is hung on two 1-7/8-inch steel cables which are anchored on one side to a rock ledge and on the other in a fifty-ton cement base. Before this bridge was constructed the method of crossing to the foot of Rocky Hollow was made in an old flatboat which saw service from 1884 to 1917.

6. Lusk’s Fill, on Trail 1 south of the Covered Bridge, was John Lusk’s attempt to build a roadbed and at the same time to construct a fish pond. This fill, which runs south and along the top of which Trail 1 runs, took three years of fruitless labor and cost many thousands of dollars. It was abandoned and the present road east of it made.

7. Gypsy Gulch and the Falls, on Trail 2, are found in the section of the park underlying the rocks on the south side of Sugar Creek. This area was known to the pioneers as the Falls. Here Salmon Lusk, John Lusk and the others for many miles around came for their picnics. In 1910 a pony called Gypsy fell over the cliff, and since then the name Gypsy Gulch has been given to the area, which is one of the most attractive in the park.

8. The Coal Mine, on Trail 2, was used by John Lusk for many years as the source of his coal supply. The shaft and the old track used in drawing the coal out is still to be seen.

9. Rocky Hollow is on Trail 4 north of the Suspension Bridge. This is the most ostentatious hollow of the park. The lower part is wide and in some places has 80-foot cliffs. Near the mouth of the hollow is Edge Rock, which many years ago fell from the cliff above. The upper part of the hollow is narrow, and steps cut in the rock are used in the passage along its rocky sides. In the upper part of Rocky Hollow is the Punch Bowl, a geological formation 15 feet across and 6 feet deep, caused by boulders being swirled around by the rushing waters at the time of the melting of the glaciers.

10. The Ice Box, on Trail 3, west of the Suspension Bridge, is an interesting glacial formation which is of circular shape and about 80 feet in depth. In it is Wedge Rock, a formation in the shape of a slice of pie.

11. Turkey Run Hollow, although not of great length, is one of the widest and most beautiful in the park. It was under the overhanging rocks of this hollow that the wild turkeys roosted in the past, and the bank and rough-winged swallows now nest in crevices in the rock. In this hollow, also, the very rare Sword Moss is to be found.

12. Boulder Canyon, on Trail 9, is in the farthest west section of the park on the north side of the creek. It is a beautiful canyon which contains the best examples in the park of the various water-worn rounded boulders deposited in the area by the receding glacial ice masses.

13. The Sycamore and Walnut Groves on Trail 1, just east of the Swinging Bridge, contain some of the finest specimens of walnut and sycamore trees in the state. The light-barked sycamore trees, with the great trunks, and the tall stately walnut trees, often with no branches for ninety feet, are the oldest inhabitants of Turkey Run.

14. The Big Tulip or Yellow Poplar, on Trail 7, is one of the finest examples of the trees most often used by the pioneer Hoosiers to construct their log cabins. Throughout the park are a number of great tulip trees. Several are to be found near the hotel.

15. Lover’s Lane and the Hawk’s Nest are on Trail 1 along the creek from the hotel to the Swinging Bridge. Here are the large trees, elms and sycamores, forming a shady canopy over the trail. From Trail 1 Hawk’s Nest, a huge exposed rocky cliff on the opposite side of the creek, illustrates the type of place utilized by hawks, phoebes and swallows as nesting sites.

PARK RULES

Visitors are requested to observe the following rules in order that we may fulfill the purposes for which state parks were established, namely: THE PRESERVATION OF A PRIMITIVE LANDSCAPE IN ITS ORIGINAL CONDITION:

1. Do not injure any structure, rock, tree, flower, bird or wild animal within the park.

2. Firearms are prohibited.

3. Dogs are to be kept on leash.

4. There shall be no vending or advertising without permission from the Department of Conservation.

5. Camps are provided. The camping fee is twenty-five (25) cents per car or tent for each twenty-four hours or fraction thereof. Please put waste in receptacles provided.

6. Fires may be built only in places provided.

7. Motor vehicles shall be driven slowly and on established roads. Park in designated places only.

8. Bathing is limited to such places and times as the Department of Conservation deems safe.

9. Drinking water should be taken from pumps and hydrants only.

The failure of any person to comply with any provision of the official regulations (published and placed in effect September 15, 1927) shall be deemed a violation thereof, and such person shall be subject to a fine as provided by act of March 11, 1919.

Trails

in

Turkey Run State Park

Conservation Department

Department of Public Works

Department of State Parks, Lands and Waters

State of Indiana

This is YOUR PARK

All visitors are expected to observe the following rules that we can fulfill the purpose for which this and other state parks were established, the preservation of a primitive landscape in its original condition and a place where you might enjoy the out-of-doors.

1. Do not injure or damage any structure, rock, tree, flower, bird or wild animal within the park.

2. Firearms are prohibited at all times.

3. Dogs must be kept on leash while in the park.

4. There shall be no vending or advertising without permission of the Department of Conservation.

5. Camping areas are provided at a fee of twenty-five cents per car or tent for each 24 hours or fraction.

6. Fires shall be built only in places provided, visitors must put waste in receptacles provided for that purpose.

7. Motorists will observe speed limits as posted in the park and park in areas designated for parking.

8. Bathing is limited to such places and times as designated by the Department of Conservation.

9. Drinking water should be taken only from pumps, hydrants or fountains provided for that purpose. This water supply is tested regularly for purity.

CONSIDER THE RESULTS IF OTHER VISITORS USE THE PARK AS YOU DO

HELP PREVENT FOREST FIRES

Build Fires only in Designated Places.

See that cigars or cigarettes are out before they are thrown away.

Break your match before you drop it.

Report any violation of fire regulations to park officials at once.

FIRE IS THE GREATEST THREAT TO OUR PARKS AND FORESTS

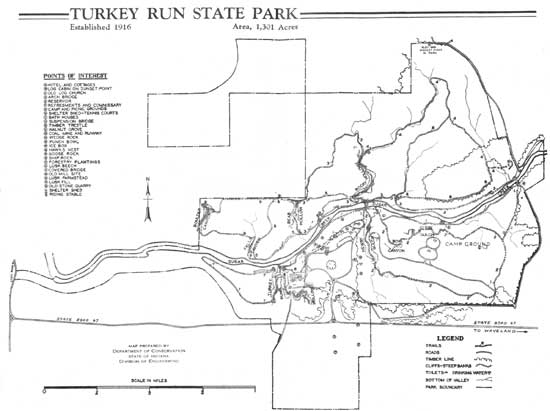

Turkey Run State Park

Established 1916

Area 1,301 Acres

Located on Road 47, near Rockville

The forerunner of Indiana’s state park system and known by thousands of visitors for its wonderful scenery and other unusual attractions. Deep gorges, cut into sandstone by action of glacial streams, provide a real thrill for the hiker with the covering of fern, moss and vine. Here, too, is a stand of virgin timber, covering an area of 285 acres and including fine specimens of tulip poplar, walnut, oak, cherry, hemlock, sycamore and maple.

Bathing facilities are maintained at a beach on Sugar Creek under the supervision of an experienced lifeguard.

TURKEY RUN INN

TURKEY RUN STATE PARK

Room and Meals $2.75 to $3.75 per day

American Plan. Meals served family style.

Weekly Rates.

The Intelligent Use Of Leisure

This trail map is given to you with the compliments of the State of Indiana through its Department of Conservation in the hope that it will direct your attention to the primary purpose for which the state park system has been established.

These recreational areas are parts of “original America,” preserving for posterity typical primitive landscapes of scenic grandeur and rugged beauty.

Along the quiet trails through these reservations it is to be expected that the average citizen will find release from the tension of his over-crowded daily existence; that the contact with nature will re-focus with a clearer lens his perspective on life values and that he may here take counsel with himself to the end that his strength and confidence is renewed.

THE DIVISION OF LANDS AND WATERS.

EACH INDIANA STATE PARK is fully equipped with all facilities for picnic parties or campers. The overnight camp fee is twenty-five cents (25¢) per car, which partly covers the cost of fuel, water and sanitary maintenance. The water is tested frequently throughout the season by the State Board of Health. Shelter houses and refreshment stands provide rest and comfort. Hotel reservations should be made by mail direct to the Inns.

A Points of Interest map showing the complete state highway system and location of each state park, memorial, game preserve, fish hatchery, and forest reservation with a more detailed description of each; likewise the location of ninety other points of interest, is free. Ask any park custodian, or write the Department of Conservation, State Library Building, Indianapolis.

INDIANA DUNES STATE PARK comprises twenty-two hundred acres of primitive, beautiful, historical and amazingly unique Hoosier landscape. It lies in Porter County and includes three miles of Lake Michigan’s south shore, all of which provides a magnificent beach capable of accommodating many thousand bathers.

Eighteen hundred acres are wooded, including swamps, and prairie bogs replete with the most diversified flora and fauna of the mid-west. Other acres are made up of drifting sand hills, peculiar to the Dunes region.

A three-story pavilion on the beach provides shelter, bath houses, and locker room, and houses cafeteria, complete restaurant and dining room service. Arcade Hotel, overlooking the lake, contains fifty sleeping rooms. Limited American plan service is available at Duneside Inn, the park’s second hotel. Concrete parking pavement on the beach accommodates twelve hundred automobiles.

CLIFTY FALLS STATE PARK comprises a portion of the rugged, majestic landscape of historic Jefferson County near Madison, where the beautiful Ohio Valley is finest. The outstanding feature of this park is the water-worn gorge where Clifty Creek drops seventy feet from a stone ledge. Trails wind through the great hollow and along the sides of precipitous vine and fern-covered cliffs, giving access to wooded ravines and lesser water-falls.

Clifty Inn is on the crest of a steep slope, four hundred feet above the Ohio River. The sweeping curves of the river, Kentucky hills far distant, and the panorama of Madison are unsurpassed, viewed from the Inn veranda. The Inn provides comfortable beds, immaculate housekeeping, and well cooked food in abundance.

POKAGON STATE PARK comprises nearly one thousand acres of the lovely, peaceful rolling landscape in Steuben County, two miles of which front Lake James. There are four hundred acres of deep woods. The big lake is a fisherman’s paradise. Buffalo, elk and deer in their native habitat, but within strong corrals, represent the larger species of wild life once native to the mid-west. Excellent boating and bathing facilities, and tennis courts, offer wholesome recreation. Saddle horses are available and an eighteen-hole golf course is located nearby.

Potawatomi Inn’s dining room seats three hundred capacity. Excellent cooking and modern guest rooms, make this an unusually popular lake park.

SPRING MILL STATE PARK of eleven hundred acres in Lawrence County, is perhaps the most unique of the state parks. Here in a beautiful little valley among heavily forested hills is the restored pioneer village of Spring Mill with its massive stone grist mill operated by a flume and overshot water wheel. The post office, general store, apothecary, nursery, distillery, saw mill and numerous residences all furnished completely in the period of our forefathers, provide a never-ending delight to park guests.

To the student of nature, the caves and subterranean streams with blind aquatic life, are great attractions. Restaurant service and refreshments are available in the quaint old log tavern.

McCORMICK’S CREEK STATE PARK in the White River valley in Owen County has within its boundaries some of the most majestic scenery of southern Indiana. The park is at the edge of the great stone belt, and is replete with ravines, gulches, and timbered slopes. Park woodlands are noted for the great profusion of wild flowers. A modern artificial swimming pool and bath house is in operation. Dormitories and mess halls for large camp groups make this park especially adapted to organization camps.

Canyon Inn, a modern structure, accommodates sixty-eight over-night guests, and serves special chicken dinners for week-end visitors.

BROWN COUNTY STATE PARK, in the heart of the mountainous hills of Brown County, has that spectacular topography of dense woods and wide, sweeping valleys, all readily accessible over modern, all-weather roads.

The Kin Hubbard Ridge development consists of a group of delightful and fully equipped cottages serviced by the Abe Martin Hall. This community group nestles in the forest fringe atop a promontory and commands an unsurpassed view of the area. The Hall provides restaurant service or staple groceries. The cottages may be rented by the week upon application.

SHAKAMAK STATE PARK lies in a triangle of Clay, Green and Sullivan Counties, offering the recreational features of rugged and wooded country. An outstanding feature of the park is a beautiful, meandering lake of fifty-five acres, affording boating and supervised bathing. The park contains a tree nursery and pheasantry, providing demonstrations in reforestation and game culture to those interested in this phase of conservation. Shakamak is equipped with dormitories and mess hall to accommodate organization camps up to a capacity of two hundred and fifty people.

MOUNDS STATE PARK, in Madison County, on the bluffs of White River, is a reservation set aside for natural recreation and preservation of a group of prehistoric earthwork monuments constructed by that vanquished American race known as Mound Builders. These mounds represent the largest and best preserved group in Indiana and are of great interest to laymen as well as archaeologists.

Excellent boating and picnic facilities are available; refreshments are obtained at the Pavilion.

MUSCATATUCK STATE PARK, in Jennings County, embraces the finest scenery, gorges and timbered slopes of the beautiful Muscatatuck River. This section of Jennings County long has been known for fine hunting and excellent fishing.

Muscatatuck Inn, with cottage rooms, provides delightful lodging and wholesome food for those seeking quiet and restful surroundings, and enjoys a wide reputation among motorists as a stop over point.

DESCRIPTION OF TRAILS

TRAIL No. 1. Along the south shore of Sugar Creek, past the swinging bridge to the covered bridge, then south to road, west along road through camp ground to hotel. This is a comparatively easy trail with few places to climb. Interesting places: Lovers’ Lane, Hawk’s Nest, the Large Elms, the Sycamore Grove, the largest Walnut in the park, Goose Rock, Ship Rock, the largest tree in the park, Lusk’s Fill. Distance—2-3/4 miles.

TRAIL No. 2. Either along Trail No. 1 or through the camp ground and down the steps at suspension bridge. From Trail 1, Trail 2 leads through Newby Gulch, across the plateau, across the road (Trails 1 and 2, at this point are together), through the woods for about one-fourth mile, then west through Gypsy Gulch and Box Canyon to swinging bridge and back to camp ground and hotel. Interesting places: The Tuffa Beds in Newby Gulch, High Bridge over Newby Gulch, overhanging Rock Cliffs in Gypsy Gulch, and Box Canyon and many beautiful ferns. Distance—3 miles.

TRAIL No. 3. Take Trail 1 to swinging bridge and cross Sugar Creek, go up Rocky Hollow (Trail 4) for about one-half mile, then west through woodlands, down the ladders in Bear Hollow, east by river, down ladders in Ladder Rock, return to swinging bridge. From this point the trail follows the north bank of Sugar Creek eastward to covered bridge and returns to the hotel along Trail 1. Interesting points: Wedge Rock, Rocky Hollow, the Coal Mine, Lusk beech, and covered bridge, Punch Bowl, Bear Hollow, the Ice Box, and Ladder Rock. Distance—2-1/2 or 4-1/2 miles.

TRAIL No. 4. Trail 1 to swinging bridge, thence to Rocky Hollow, turning at the head of the Hollow through woods to Lusk Home on the hill above the Narrows, back to camp ground or hotel by way of Trail 8 or Trail 3 along Sugar Creek to swinging bridge. Interesting points: Rocky Hollow, Yew Trees, Wedge Rock, Punch Bowl, Lusk Home, the Old Mill Site, the Covered Bridge, and the Coal Mine. Distance—3-1/2 miles.

TRAIL No. 5. Starting point the same as Trail 3. Trail 5 branches out from Trail 3 and extends for some distance west of Trail 3 by routing through the woods. Instead of going up Rocky Hollow, Trail 5 can be reached on Trail 3 by going west from swinging bridge up through Ladder Rock. Interesting points: The Ice Box, beautiful woodland scenes with ferns and flowers. Distance—4 miles.

TRAIL No. 6. From Sunset Point down to Turkey Run Hollow, up Hollow to road. This is the shortest trail in the park. Interesting points: The Overhanging Cliffs, under which the wild turkeys came to roost, the Arch Bridge over Turkey Run Hollow, and Sword Moss which is found only in a few places in North America. Distance—1/2 mile.

TRAIL No. 7. From Sunset Point down into the Hollow, west up cliff, around Inspiration Point through woods, and down the Hollow to Sunset Point. Interesting points: Mosses, Walking Ferns, and Yew trees, good view of Sugar Creek and Overhanging Cliffs. Distance—3/4 mile.

TRAIL No. 8. Along Trail 1, to swinging bridge. Cross bridge, go east along creek to coal mine, then north on Trail 8 to junction with 4, east (right) through woods to Lusk Home, west along the edge of field to Coal Mine and Trail 3 to swinging bridge. Interesting points: Coal Mine, ferns, flowers, Lusk Home, Narrows, Mill Site. Distance—3-1/4 miles.

TRAIL No. 9. This is the longest and most arduous hike in the park, for in order to reach Trail 9, parts of Trails 3 and 5 must be taken. Trail 9 extends from Trail 5 west through Falls and Boulder Canyons. Interesting points: The Glacial Boulders, deposited many years ago when the great glaciers from the north covered this area. Many of the same points seen on Trails 3 and 5. Distance—4 miles (via Ladder Rock); 4-1/2 miles (via Rocky Hollow).

Interested in other State Parks?

Click here for a great Indiana State Parks Guide.